Including Spirituality Into a Fuller Picture of Research on Whole Person Health

Director’s Page

Helene M. Langevin, M.D.

August 18, 2023

Does health have a spiritual dimension? For many, the answer is yes. As the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) team looks ahead to the development of our next strategic plan, I hope to get a conversation started about how we may thoughtfully include spirituality as one of the domains of research on whole person health.

As we strive to better understand the components of overall health, we’ll need to answer a core question. What are the elements of spiritual health that would be most amenable to research and would interconnect with the biological, behavioral, social, and environmental domains that we study? Although it will be challenging to define data elements and research methods related to spirituality, I am encouraged by recent discussions with our Advisory Council on this issue and with our interactions with the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation, which has put spirituality front and center in their Whole Health patient care model.

Positive spiritual experiences are often defined as a sense of oneness and connection to others, a higher power, or the natural world. Spirituality is often linked to a sense of meaning and purpose in life, which also represents connections. Spiritual “unhealth,” in contrast, could be viewed as disconnection, a sense of isolation, unmooring, or hopelessness.

Spiritual disconnects may manifest in human relationships; for example, in the isolation that most of us experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and the alarming current “epidemic” of loneliness highlighted by the U.S. Surgeon General. Spiritual disconnects can also manifest in our relationship with the natural world. People are increasingly impacted by the destabilization of our environment, but also may feel powerless to create change. The spiritual impact may be most acutely felt within tribal communities—American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Canadian First Nations—which traditionally have strong ties to the natural world. In my recent address at the Nova Institute for Health Annual Conference, I argued that because human health and planetary health are inextricably linked, research on whole person health, to be fully effective, will need to include the connections of individuals to one another as well as to the planet as a whole.

Being human means being aware of our separateness and temporary existence. From birth and throughout our lives, we all yearn to bridge this separateness. All major religions throughout the world share a component of reconnection, to create meaning that helps heal our sense of isolation. The human need to connect with something larger than ourselves is vividly illustrated in what researchers call the “overview effect,” a profound cognitive and emotional shift in a person's awareness, consciousness, and identity when they see the Earth from space. Astronauts often return from space more convinced of the interconnectedness of humanity and filled with a desire to do something to improve life on the planet.

Contemplative practices such as meditation have been striving to expand this type of human awareness for millennia. Interestingly, the recent resurgence of interest in the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin illustrates the varied pathways to spiritual experiences that we are just beginning to understand physiologically. Researchers have found that patients with intractable depression who receive these drugs under medical supervision describe profound and lasting shifts in awareness and sense of “oneness” with the world.

Acquiring a sense of connection, meaning, and purpose is a part of spiritual growth. Patients who experience a severe trauma or a life-threatening illness such as cancer often describe a renewed sense of appreciation for life. Post-traumatic growth is indeed related to the concept of resilience, allowing an individual to not only recover from a challenge but also grow in strength. At the VHA, the Whole Health model is centered on encouraging patients to define “what matters most to them” and center their care around this awareness to define health goals.

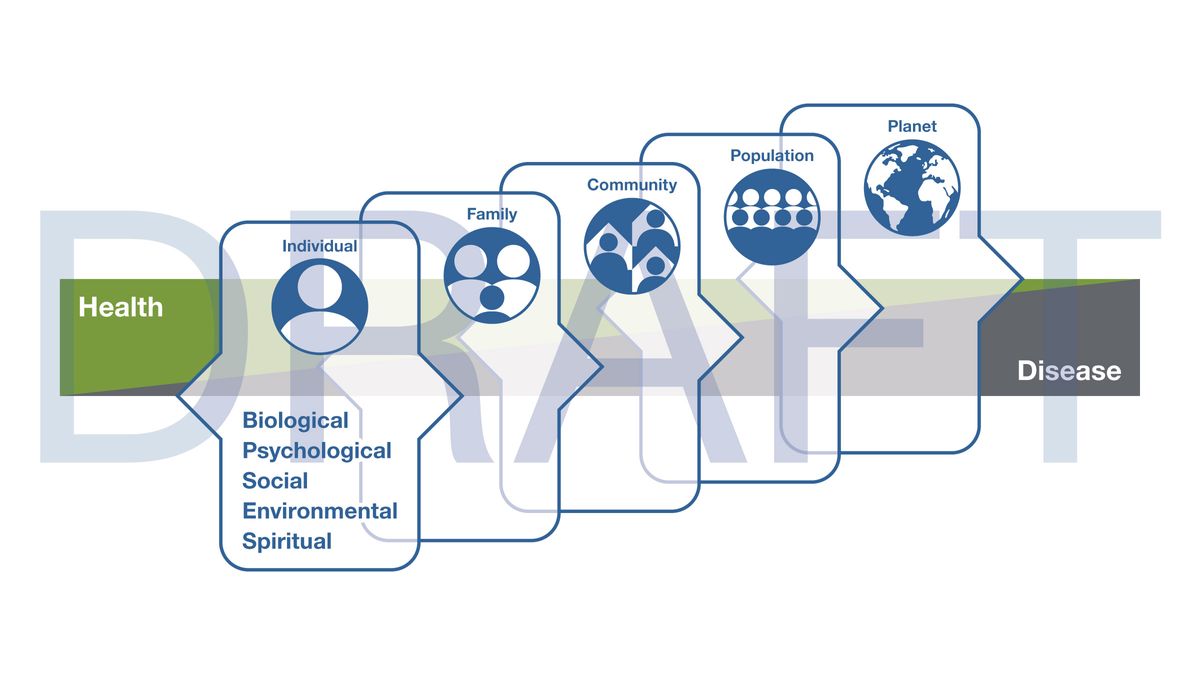

Looking ahead, it will be important to better understand how spiritual interconnectedness can be strengthened through the basic biological mechanisms of practices that focus on expanding awareness, such as meditation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and other traditional healing practices. NCCIH’s robust portfolio of such research—for example, on resilience and emotional well-being in the context of recovery from substance use—serves as a natural basis for more explicitly including spirituality as a component of whole person health. And doing so is a logical next step in our effort to define the full scope of research on whole person health. I look forward to exploring how to best deploy a spectrum of research aimed at promoting and restoring the health of individuals, families, populations, and the planet across biological, behavioral, social, environmental, and spiritual domains (see draft figure below).

If you have thoughts you would like to share on this topic, please send an email to NCCIHStrategicPlan@mail.nih.gov. We look forward to hearing many perspectives and continuing a fruitful discussion.